History in New France (Canada)

Table of Contents

New France between 1656 and 1716

Early Exploration

Foundation of Québec

Royal Control

Fall of New France

Francois Bibaud in Trois-Rivieres,

New France – 1656 to 1671

Francois Bibaud – The Pageant of 1671

Francois Bibaud and Jeanne (Chalifou) Bibaud – 1671 to 1682

Francois and Louise (Esnard) Bibaud

– 1682 to 1716

New France between 1691 and 1847

Nicolas and Marguerite Bibaud

(Emily’s 4x great grandparents)

Joseph and Marie Anne Bibaud (Emily’s

3x great grandparents)

Joseph Alexis and Marie Bibeau (Emily’s 2x great grandparents)

Parish of St-Francois-Xavier,

Batiscan, Quebec

Parish of

St-Francois-Xavier, St-Francois-du-Lac, Quebec

Parish of St-Pierre-de-Sorel, Sorel,

Quebec

For photos of the area

our Bibeau ancestors lived in the province of Quebec, see this photo album. These photos were taken in August 2006 during

a week long trip to Quebec City, Montreal and the area in between along the St.

Lawrence River.

New France between 1656 and 1716

New France in the late

1600’s

What is meant by “New France” and what was

it like when our ancestor, Francois Bibaud, arrived in 1656? According to Wikipedia (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_France):

New France (in French

“la Nouvelle-France”) describes the area colonized by France in North America

during a period extending from the exploration of the Saint Lawrence River by

Jacques Cartier in 1534 to the cession of New France to the Kingdom of Great

Britain in 1763.

At its peak in

1712 (before the Treaty of Utrecht), the territory of New France extended from

Newfoundland to Lake Superior and from the Hudson Bay to the Gulf of Mexico.

The territory was then divided in five colonies, each with its own

administration: Canada, Acadia, Hudson Bay, Newfoundland and Louisiana.

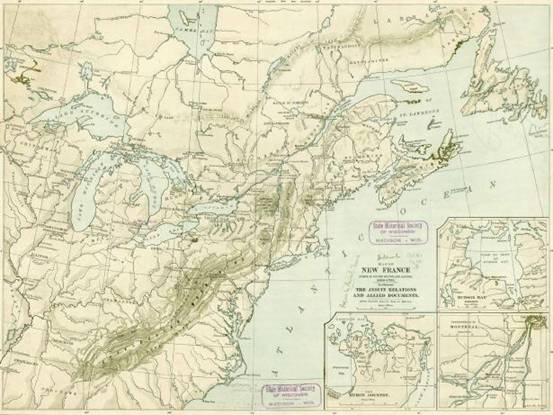

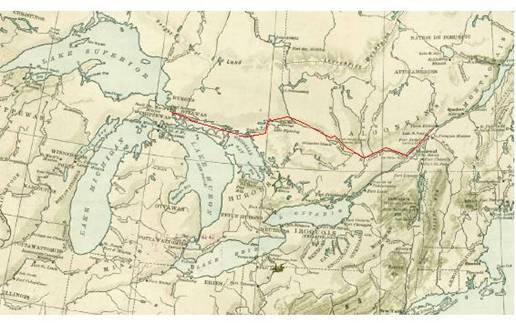

This is a map of

New France between 1610 and 1791:

Source: Wisconsin State Historical

Society, from http://www.myerchin.org/Resources/New%20France%20Map.pdf

Early Exploration

In 1524, Italian

navigator Giovanni de Verrazzano explored the eastern shore and named the new

lands Francesca, in honor of King Francis I of France. In 1534, Jacques Cartier

planted a cross in the Gaspé peninsula and claimed the land in the name of King

Francis I. However, France was initially not interested in backing up these

claims with settlement. French fishing fleets, however, continued to sail to

the Atlantic coast and into the St. Lawrence River, making alliances with First

Nations that would become important once France began to occupy the land.

French merchants soon realized the St. Lawrence region was full of valuable

fur, especially beaver fur, which was becoming rare in Europe as the European

beaver had almost been driven to extinction. Eventually, the French crown

decided to colonize the territory to secure and expand its influence in

America.

The vast

territories that were to be known as Acadia and Canada were in some areas

inhabited by nomadic Amerindian peoples or settlements of Hurons and Iroquois.

These lands were full of unexploited and valuable natural riches which

attracted all of Europe. By the 1580s, French trading companies had been set

up, and ships were contracted to bring back furs. Much of what has happened

between the natives and the European visitors around that time is not known for

lack of historical records.

Early attempts at

establishing permanent settlements were failures. In 1598 a trading post was

established on Sable Island, off the coast of Acadia, but was unsuccessful. In

1600, a trading post was established at Tadoussac, but only five settlers

survived the winter. In 1604 a settlement was founded at Île-Saint-Croix on

Baie François (Bay of Fundy) which was moved to Port-Royal in 1605, only to be

abandoned in 1607, reestablished in 1610 and destroyed in 1613 whereby settlers

moved to other nearby locations.

Foundation of

Québec

In 1608,

sponsored by Henry IV of France, Samuel de Champlain founded Québec with six

families totalling 28 people, the first successful settlement in Canada. Colonization

was slow and difficult. Many settlers died early. In 1630 there were only 100

colonists living in the settlement, and by 1640 there was 359.

Champlain quickly

allied himself with the Algonquian and Montagnais peoples in the area, who were

at war with the Iroquois.He established strong bonds with the Hurons in order

to keep the fur trade alive. He also arranged to have young French men live

with the natives, to learn their language and customs and help the French adapt

to life in North America. These men, known as Voyageurs, such as Étienne Brûlé,

extended French influence south and west to the Great Lakes and among the Huron

tribes who lived there.

For the first few

decades of Québec's existence, there were only a few dozen settlers there,

while the English colonies to the south were much more populous and wealthy.

Cardinal Richelieu, adviser to King Louis XIII, wished to make New France as

significant as the English colonies. In 1627 Richelieu founded the Company of

One Hundred Associates to invest in New France, promising land parcels to

hundreds of new settlers and to turn Québec into an important mercantile and

population colony. Champlain was named Governor of New France, and Richelieu

forbade non-Roman Catholics from living there. Protestants were required to

renounce their faith to establish themselves in New France; many chose instead

to move to the English colonies. The Roman Catholic Church, and missionaries

such as the Recollets and the Jesuits, became firmly established in the

territory. Richelieu also introduced the seigneurial system, a semi-feudal

system of farming that remained a characteristic feature of the St. Lawrence

valley until the 19th century.

At the same time,

however, the English colonies to the south began to raid the St. Lawrence

valley, and in 1629 Québec itself was captured and held until 1632. Champlain

returned to Québec that year, and requested that Sieur de Laviolette found

another trading post at Trois-Rivières in 1634. Champlain died in 1635.

The Church, which

after Champlain’s death was the most dominant force in New France, wanted to

establish a utopian Christian community in the colony. In 1642, they sponsored

a group of settlers led by Paul Chomedey de Maisonneuve who founded

Ville-Marie, precursor to present-day Montreal, further up the St. Lawrence.

Throughout the 1640s, Jesuit missionaries penetrated the Great Lakes region and

converted many of the Huron natives. The missionaries came into conflict with

the Iroquois, who frequently attacked Montreal. By 1649 both the Jesuit mission

and Huron society in general were almost completely destroyed by Iroquois

invasions.

Royal Control

In the 1650s,

Montreal still had only a few dozen settlers and a severely underpopulated New

France almost fell completely to the Iroquois attempts to drive the French out.

In

1656, our ancestor, Francois Bibaud immigrated to New France and settled in

Trois Rivieres (Three Rivers) located on the Saint Lawrence River, half way

between Quebec and Montreal.

In 1660, settler

Adam Dollard des Ormeaux led a Canadian and Huron militia against a much larger

Iroquois force; none of the Canadians survived. In 1663 New France finally

became more secure when Louis XIV made it a province of France. In 1665 he sent

a French garrison, the Carignan-Salières regiment, to Québec. The government of

the colony was reformed along the lines of the government of France, with the

Governor General and Intendant subordinate to the Minister of the Marine in

France. In 1665, Jean Talon was sent by Minister of the Marine Jean-Baptiste

Colbert to New France as the first Intendant. These reforms limited the power

of the Bishop of Québec, who had held the greatest amount of power after the

death of Champlain.

The 1666 census

of New France was conducted by France's intendant, Jean Talon in the winter of

1665-1666. It showed a population of 3215 habitants in New France, many more

than there had been only a few decades earlier. But the census showed a great

difference in the number of men (2034) and women (1181). As a result, and

hoping to make the colony the centre of France's colonial empire, Louis XIV

decided to dispatch more than 700 single women, aged between 15 and 30 (known

as les filles du roi) to New France. At the same time, marriages with the

natives were encouraged and indentured servants, known as engagés, were also

sent to New France. One such engagé, Etienne Trudeau, was the ancestor of

future Prime Minister of Canada Pierre Elliott Trudeau.

Talon also tried

to reform the seigneurial system, forcing the seigneurs to actually reside on

their land, and limiting the size of the seigneuries, in an attempt to make

more land available to new settlers. These schemes were ultimately

unsuccessful. Very few settlers arrived, and the various industries established

by Talon did not surpass the importance of the fur trade.

Since Henry

Hudson claimed Hudson Bay, James Bay and surrounding territory for the English,

they had began expanding their boundaries across what is now the Canadian north

beyond the French-held territory of New France. In 1670, with the help of

French coureurs des bois, Pierre-Esprit Radisson and Médard des Groseilliers,

the Hudson's Bay Company was established to control the fur trade in all the

land that drained into Hudson Bay. This ended the French monopoly on the

Canadian fur trade. To compensate, the French extended their territory to the

south, and to the west of the American colonies. In 1682, René Robert Cavelier,

Sieur de La Salle explored the Ohio and Mississippi valleys, and claimed the

entire territory for France as far south as the Gulf of Mexico. He named this

territory Louisiana. Although there was virtually no colonization in this part

of New France, there were many strategic forts built there, under the orders of

Governor Louis de Buade de Frontenac. Forts were also built in the older

portions of New France that had not yet been settled.

In 1689 the

English and Iroquois began an assault on New France, after many years of minor

skirmishes throughout the English and French territories. This war, known as

King William's War, ended in 1697, but a second war (Queen Anne's War) broke

out in 1702. Québec survived the English invasions of both these wars, but Port

Royal and Acadia fell in 1690.

In 1713 peace

came to New France with the Treaty of Utrecht. Although the treaty turned

Newfoundland and part of Acadia (peninsular Nova Scotia) over to Britain,

France remained in control of Île Royale (Cape Breton Island) and Fortress

Louisbourg, as well as Île Saint-Jean (Prince Edward Island) and part of what

is today New Brunswick.

After the treaty,

New France began to prosper. Industries, such as fishing and farming, that had

failed under Talon began to flourish. A "King’s Highway" was built

between Montreal and Québec to encourage faster trade. The shipping industry

also flourished as new ports were built and old ones were upgraded. The number

of colonists greatly increased, and by 1720 Québec had become a self-sufficient

colony with a population of 24,594 people. The Church, although now less

powerful than it had originally been, had control over education and social

welfare. These years of peace are often referred to by the French as New

France's "Golden Age" but the aboriginal peoples regarded it as the

continued decimation of their nations.

Peace lasted

until 1744, when William Shirley, governor of Massachusetts, led an attack on

Louisbourg. Both France and New France were unable to relieve the siege, and

Louisbourg fell. France attempted to retake the fortress in 1746 but failed. It

was returned under the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle, but this did not stop the

warfare between the British and French in North America.

In 1754 the

French and Indian War began as the North American phase of the Seven Years' War

(which did not technically begin in Europe until 1756), with the defeat of a

small army led by Colonel George Washington by the French militia in the Ohio

valley.

Fall of New

France

New France now

had over 50,000 inhabitants, a vast increase from earlier in the century, but

the British American colonies greatly outnumbered them with over one million

people (including a substantial number of French Huguenots). It was much easier

for the British colonists to organize attacks on New France than it was for the

French to attack the British. In 1755 General Edward Braddock led an expedition

against the French Fort Duquesne, and although they were numerically superior

to the French militia and their Indian allies, Braddock's army was routed and

Braddock was killed.

In 1758 Great

Britain again captured Louisbourg, allowing them to blockade the entrance to

the St. Lawrence River. This was essentially the death sentence of New France.

In 1759 the British besieged Québec by sea, and an army under General James

Wolfe defeated the French under General Louis-Joseph de Montcalm at the Battle

of the Plains of Abraham in September. The garrison in Québec surrendered on

September 18, and by the next year New France had been completely conquered by

the British. The last French governor-general of New France, Pierre Francois de

Rigaud, Marquis de Vaudreuil-Cavagnal, surrendered to British Major General

Jeffrey Amherst on September 8, 1760. France finally ceded Canada to the

British in the Treaty of Paris, signed on February 10, 1763.

French culture

and religion remained dominant in most of the former territory of New France,

until the arrival of British settlers led to the later creation of Upper Canada

(today Ontario) and New Brunswick. The Louisiana Territory, under Spanish

control since the end of the Seven Years' War, remained off-limits to

settlement from the 13 American colonies. Following Napoleon Bonaparte's defeat

of Spain, he took back the Louisiana Territory and in 1803 sold it to the new

United States. This sale represented the end of the French colonial empire in

North America except for the islands of St. Pierre and Miquelon which it still

controls to this day.

Francois

Bibaud in Trois-Rivieres, New France – 1656 to 1671

When Francois Bibaud arrived in New France in 1656, he settled

in Trois-Rivieres (Three

Rivers) located on the Saint Lawrence River, half way between Quebec and

Montreal. This was in compliance with the terms of his Contract of Servitude in

France.

Source: Wisconsin State Historical

Society, from http://www.myerchin.org/Resources/New%20France%20Map.pdf

It did not take Francois long to realize that the only trade which was profitable was the one of fur trading. Thus, Francois became a “Coureur-de-Bois” also known as a wood-runner or a bushranger. He adventured with a few friends to the most remote regions where they did business with the Indians. In exchange for brandy, or any other similar beverages, as well as items such as knives, mirrors etc., the French men received furs of great value.

The life of the bushrangers had great benefits, but also great risks. Lost in the deepest forests, remote from all civilization, the wood-runners could not count on any help from anyone, nor did the law protect them. They would go from tribe to tribe, sometimes in great friendship with the Indians who sometimes welcomed them with open arms, but often enough they had to leave their scalps behind if not their lives in some of the largest villages.

The trade of the coureur-de-bois was allowed at the beginning of the colony. But in 1774, in its attempt to regulate the trade with the Indians, the government of New France prohibited traders from going to the Indian country. Therefore, the Indians themselves would bring their furs on the St. Lawrence where the exchange with the French men was permitted.

Francois Bibeau, occupied himself with the fur trade for ten years, from 1661-71. He would always settle his affairs on his return from his courses. During this time, he seems to have lived or had land concessions in various places along the St. Lawrence River, half way between Quebec and Montreal, in the district of Trois-Rivieres, the county of Champlain.

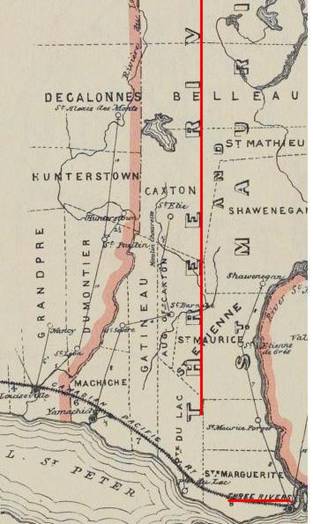

Source (map from

1865): http://www.collectionscanada.ca/archivianet/020151/0201510403_e.html

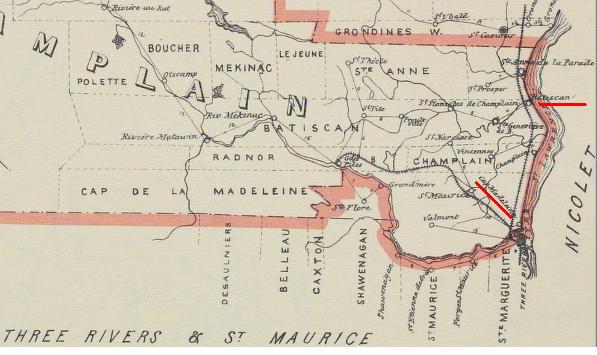

In the county of Champlain, located on the west bank of the St. Lawrence River, Francois lived or had land in Cap-de-la-Madeleine, Batiscan, Côte Saint Marc, and Côte Saint Eloy.

Source: 1911 map, county of Champlain

http://www.collectionscanada.ca/archivianet/1911/006003-380.09-e.html

Various legal documents allow us to trace his activities from 1660-1671, as follows.

On 10 September 1660, Quentin Moral

submitted a claim to Francois for himself and three other men, Pierre Trottier,

François Duclos and Mathurin Guichart, for some damages and interest because

Francois was not able to provide them his boat for transporting 200-300 sheaves

of wheat. (Archives. Quebec Prevote of

Three Rivers).

On 17 March 1661, Francois lived at Cap

de la Madeleine and visited the notary Claude Herlin where he signed the

Nadaud contract.

On 27 June 1662, Francois was in Cap de

la Madeleine in the notary L. Laurent's office where he signed an act, giving

power of attorney to Jean Gladu to receive from his debtors the amounts due

him, which were: from Pierre Boussoi, 19

livres and 10 sols, from Bourbeau, 40 sols and one new tie from Holland,

estimated at 60 sols by the wife of Bourbeau, from Louis Lefebvre called

Lagroix, 100 sols for some work, and from Pierre Guillet called Lajeunesse, 4

livres for some work. He also authorized

his agent to sell a pair of snow shoes, an axe, a hoe, a chain for towing and

his furniture.

On 15 July 1662, at Côte Saint-Marc,

Francois purchased a dwelling and some land approximately two acres wide and

twenty acres deep from Père Claude Aloué, a Jesuite priest.

On 31 March 1664, he was in Trois-Rivieres

at the notary Larue's, this time signing a contract with Elie Bourbeau, Pierre

Guillet, and the two brothers Antoine and Julien Trotier.

In 1665 Francois was living at Côte Saint-Marc.

On 29 October 1665, at Cap de la Madeleine, Francois signed his first contract of marriage before the notary Jacque De La Touche, for marriage with Jeanne Merine. Jeanne Merine was a “fille du roi” whose parents were Jean Merine at Marie La Haye. A “fille du roi” (daughter of the king) was not a relation of the king but a young woman sponsored by the French government to go to Nouvelle France for marriage and colonization purposes. This marriage contract was not concluded and was cancelled one year later on 29 October 1666. As such, Jeanne Merine did not legally become his wife.

Further information on

marriage contracts can be found at:

Betrothols: http://www.phatnav.com/wiki/index.php?title=Betrothal

History of marriages:

http://www.drizzle.com/~celyn/mrwp/mrwed.html

Up to 1666 Bibeau had lived on Côte St-Marc

but on 6 April 1666, Father Frémin, a Jesuite priest, ceded him two habitations

of two acres by forty each (notary Latouche) at:

- Batiscan, between Francois Lary dit

Gargot at S.W. and Nicolas Rivard at N.E.

- Côte Saint-Éloy, between Francois

Duclos at S.W. and Jean Trotier N.E.

On 25 December 1666 Francois yielded his land at Côte St-Marc (also two acres by forty) to Rene Blanchet for 40 livres. The neighbors were Pierre Menard S.W. and Benjamin Anseau S.E. (notary Latouche).

Although a landowner, Francois Bibeau was

hiring out his services as a servant to Elie Bourbeau in 1667 (Census in

Sulte's).

On 15 September 1668, Francois exchanged his dwelling at Cap de la Madeleine, two acres wide by forty acres deep, for a neighbor’s of the same dimensions belonging to Nicolas Rivard dit Lavigne.

On 25 September 1668, he gifted half of his dwelling at Saint-Éloy to Pierre Bourbeau and then returned to the area of Quebec.

Francois seemed to enjoy and profit from his voyages into the

wilderness, regardless of the associated dangers. He took full advantage of this life of

adventure and travel for the first 12 years in New France. When he was about 36 years old he decided to

marry again.

As a result, on 29 October 1668, Francois signed a second marriage contract, before the notary Vachon, this time for marriage with Jeanne Chalifou. While this was Francois’ second marriage contract, Jeanne Chalifou was his first legal wife. She was born in Quebec on 22 February 1654 and was the daughter of Paul Chalifou and Jacquette Archambault. She was only 14 years old when she was engaged to Francois. They were eventually married almost three years later in Quebec on 17 August 1671. This was after Francois’ long voyage to Outaouais, or Ottawa (area west of Montreal, north of the Outaouasi River).

In late 1668 Francois began preparing himself for this voyage. As part of these preparations, he decided to provide for his future wife in the event that he did not return. Therefore, on 15 January 1669, he made a will with his future wife, Jeanne Chalifou as beneficiary, leaving her all his furniture and promising her 400 livres.

Francois Bibaud – The Pageant of 1671

In the spring of 1669, Francois Bibaud undertook the longest, and the most perilous voyage of his career as a “coureur-de-bois.” In doing so he claimed a place in history through his participation in a ceremony known as the “Pageant of 1671” at Sault Ste. Marie in modern day Michigan, USA. It was at this ceremony that France proclaimed to the world its right to the interior of the North American continent.

(The following is from the Wisconsin

Historical Society, http://www.americanjourneys.org/aj-050/summary/index.asp):

In 1664 and 1665 the King of France, Louis XIV, sent three very able men to govern New France:

· Marquis de Tracy, military commander of New France.

· Sieur de Courcelle, governor of New France.

· Jean Baptiste Talon, the Royal Intendant of New France.

Talon was charged with encouraging agriculture, establishing a royal shipyard, starting a brewery, and setting New France on a strong economic footing.

(The following is

from Frances Parkman, 1870, Chapter IV, 1667-1672 – France Takes Possession

of the West. France and England in North America, A Series of Historical Narratives,

Part Three. The Discovery of the Great West. Retrieved from www.fullbooks.com/France-and-England-in-North-America-a-Series1.html)

While laboring strenuously to develop the industrial resources of the colony, he addressed himself to discovering and occupying the interior of the continent; controlling the rivers, which were its only highways; and securing it for France against every other nation. On the east, England was to be hemmed within a narrow strip of seaboard; while, on the south, Talon aimed at securing a port on the Gulf of Mexico, to hold the Spaniards in check, and dispute with them the possession of the vast regions which they claimed as their own. But the interior of the continent was still an unknown world. It behooved him to explore it; and to that end he availed himself of Jesuits, officers, fur-traders, and enterprising schemers like La Salle.

(The following is

from Mansfield J. B., 1899, Struggle

for Possession. History

of the Great Lakes Volume I.

Chicago, IL: J.H. Beers & Co.,

Retrieved from www.hhpl.on.ca/GreatLakes/Documents/HGL/default.asp?ID=c008)

The formation of the

Hudson Bay Company in England, and the fear that the English would thereby gain

a foothold in the trade of the Great Lakes, was another cause of anxiety to the

government of New France. Talon learned in 1670 that two English vessels were

engaged in the fur trade on Hudson Bay. It was accordingly resolved to take

formal possession of the lake regions and make a closer alliance with the

tribes surrounding the lakes.

(The following is

from the Wisconsin Historical Society)

So, Talon brought orders from France to arrange an official pageant that would both impress the Indians and proclaim to the world France's right to the interior of the North American continent.

Talon chose the Jesuit mission at Ste Mary of the Falls (Sault Ste. Marie), in present day Michigan, USA, to stage the ceremony because of its commanding position at the head of the Great Lakes.

On 3 Sep 1670, Talon appointed Simon Francois Daumont, Sieur de St. Lusson, to coordinate the expedition to the mission. According to the official minutes (Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin, Vol. 11, p. 26-28, 1888-1931; http://memory.loc.gov), Talon instructed St. Lusson “to proceed forthwith to the countries of the Outaouacs, Nespercez, Illinois and other nations discovered and to be discovered in North American near Lake Superior or the Fresh Sea, to make search and discovery there for all sorts of Mines, particularly that of Copper, commanding us moreover, to take possession, in the King’s name, of all the country inhabited and uninhabited wherever we should pass…”

Two French explorers, Nicolas Perrot and Louis Jolliet, were to play key roles in the organization of this pageant.

(The following is

from Frances Parkman, 1870):

When, in 1670, Talon

ordered Daumont de St. Lusson to search for copper-mines on Lake Superior, and,

at the same time, to take formal possession of the whole interior for the king;

it was arranged that he should pay the costs of the journey by trading with the

Indians.

St. Lusson set out

with a small party of men, and Nicolas Perrot as his interpreter.

Among Canadian “voyageurs” few names are so conspicuous as that of Perrot; not because there were not others who matched him in achievement, but because he could write, and left behind him a tolerable account of what he had seen.

Perrot was at this

time twenty-six years old, and had formerly been an “engagee” of the Jesuits.

He was a man of enterprise, courage, and address; the last being especially

shown in his dealings with Indians, over whom he had great influence. He spoke

Algonquin fluently, and was favorably known to many tribes of that family.

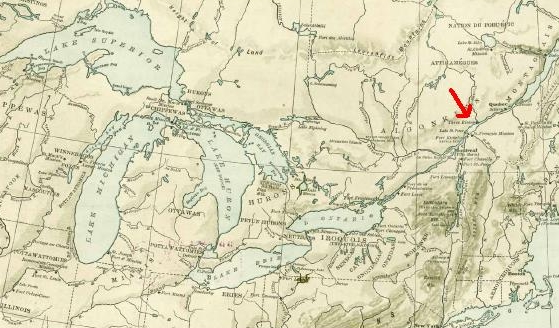

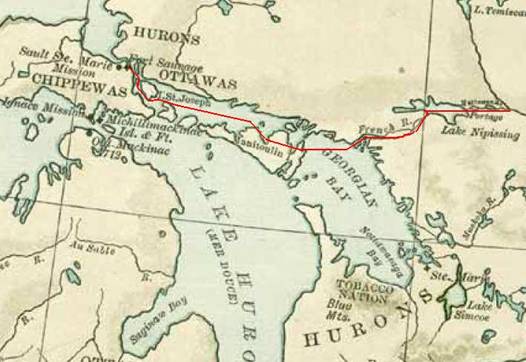

Leaving Quebec, and passing by Trois

Rivieres, they traveled up the St.-Lawrence River as far as Montreal, and from

there up the flow of the Outaouais to Nipissing Lake. Finally, they passed through the French

River, situated south of Lake Nipissing, and arrived at Lake Huron.

Source: Wisconsin State Historical

Society, from http://www.myerchin.org/Resources/New%20France%20Map.pdf

(The following is

from Frances Parkman, 1870):

St. Lusson wintered at

the Manatoulin Islands in Lake Huron, while Perrot--having first sent messages

to the tribes of the north, inviting them to meet the deputy of the Governor at

the Sault Ste. Marie (Ste. Mary of the Falls) in the following spring--proceeded to Green

Bay, to urge the same invitation upon the tribes of that quarter.

Source: Wisconsin State Historical

Society, from http://www.myerchin.org/Resources/New%20France%20Map.pdf

(The following is

from Frances Parkman, 1870):

The tribes in Green

Bay knew Perrot well, and greeted him with clamors of welcome. The Miamis, it

is said, received him with a sham battle, which was designed to do him honor,

but by which nerves more susceptible would have been severely shaken. They

entertained him also with a grand game of “la crosse”, the Indian ball-play.

Perrot gives a marvellous account of the authority and state of the Miami

chief; who, he says, was attended day and night by a guard of warriors,--an

assertion which would be incredible were it not sustained by the account of the

same chief given by the Jesuit Dablon.

Of the tribes of the

Bay, the greater part promised to send delegates to the Sault; but the

Pottawattamies dissuaded the Miami potentate from attempting so long a journey,

lest the fatigue incident to it might injure his health; and he therefore

deputed them to represent him and his tribesmen at the great meeting. Their

principal chiefs, with those of the Sacs, Winnebagoes, and Menomonies,

embarked, and paddled for the place of rendezvous [Sault Sainte Marie], where

they and Perrot arrived on 5 May 1671.

St. Lusson was [already at Sault Sainte

Marie] with his men, fifteen in number, among whom was Louis Joliet, and our ancestor, Francois Bibaud.

The Indians were fast thronging in from their wintering grounds; attracted, as usual, by the fishery of the rapids, or moved by the messages sent by Perrot,-- Crees, Monsonis, Amikou, Nipissings, and many more.

When fourteen tribes, or their representatives, had arrived, St. Lusson prepared to execute the commission with which he was charged.

Simon-François

Daumont of Saint-Lusson taking possession of the Pays d'en haut in the name of

the King of France, 14 June 1671

(From Jefferys, Charles W., 1934, Simon-François

Daumont of Saint-Lusson taking possession of the Pays d'en haut in the name of

the King of France, 14 June 1671. Canada's Past in Pictures. Toronto, Ottawa, Canada: The Ryerson Press, 52. Retrieved from Université d'Ottawa, CRCCF,

Collection générale du Centre de recherche en civilisation

canadienne-française, www.uottawa.ca/academic/crccf/passeport/I/IA1c/IA1c01-1.html

(The following is

from Frances Parkman, 1870):

At the foot of the rapids was the village of the Sauteurs, above the village was a hill, and hard by stood the fort of the Jesuits. On the morning of the fourteenth of June, St. Lusson led his followers to the top of the hill, all fully equipped and under arms. Here, too, in the vestments of their priestly office, were four Jesuits,--Claude Dablon, Superior of the Missions of the Lakes, Gabriel Druilletes, Claude Allouez, and Louis Andr? All around, the great throng of Indians stood, or crouched, or reclined at length, with eyes and ears intent. A large cross of wood had been made ready. Dablon, in solemn form, pronounced his blessing on it; and then it was reared and planted in the ground, while the Frenchmen, uncovered, sang the “Vexilla Regis”. Then a post of cedar was planted beside it, with a metal plate attached, engraven with the royal arms; while St. Lusson's followers sang the “Exaudiat” [20th Psalm] and one of the Jesuits uttered a prayer for the king. St. Lusson now advanced, and, holding his sword in one hand, and raising with the other a sod of earth, proclaimed [three times] in a loud voice:

In the name of

the Most High, Mighty, and Redoubted Monarch, Louis, Fourteenth of that name,

Most Christian King of France and of Navarre, I take possession of this place,

Sainte Marie du Sault, as also of Lakes Huron and Superior, the Island of

Manatoulin, and all countries, rivers, lakes, and streams contiguous and

adjacent thereunto; both those which have been discovered and those which may

be discovered hereafter, in all their length and breadth, bounded on the one

side by the seas of the North and of the West, and on the other by the South

Sea: declaring to the nations thereof that from this time forth they are

vassals of his Majesty, bound to obey his laws and follow his customs:

promising them on his part all succor and protection against the incursions and

invasions of their enemies: declaring to all other potentates, princes,

sovereigns, states and republics,--to them and their subjects,--that they

cannot and are not to seize or settle upon any parts of the aforesaid

countries, save only under the good pleasure of His Most Christian Majesty, and

of him who will govern in his behalf; and this on pain of incurring his

resentment and the efforts of his arms. Long live the King! (Vive le Roy!)

The Frenchmen fired their guns and shouted

"Vive le Roy," and the yelps of the astonished Indians mingled with

the din.

When the uproar was over, Father Allouez

addressed the Indians in a solemn harangue; and these were his words:

It is a good work, my brothers, an important work, a great work, that brings us together in council to-day. Look up at the cross which rises so high above your heads. It was there that Jesus Christ, the Son of God, after making himself a man for the love of men, was nailed and died, to satisfy his Eternal Father for our sins. He is the master of our lives; the ruler of Heaven, Earth, and Hell. It is he of whom I am continually speaking to you, and whose name and word I have borne through all your country.

But look at this

post to which are fixed the arms of the great chief of France, whom we call

King. He lives across the sea. He is the chief of the greatest chiefs, and has

no equal on earth. All the chiefs whom you have ever seen are but children

beside him. He is like a great tree, and they are but the little herbs that one

walks over and tramples under foot. You know Onontio, [Indian name of the

Governor of Canada] that famous chief at Quebec; you know and you have seen

that he is the terror of the Iroquois, and that his very name makes them

tremble, since he has laid their country waste and burned their towns with

fire. Across the sea there are ten thousand Onontios like him, who are but the

warriors of our great King, of whom I have told you. When he says, 'I am going

to war,' everybody obeys his orders; and each of these ten thousand chiefs

raises a troop of a hundred warriors, some on sea and some on land. Some embark

in great ships, such as you have seen at Quebec. Your canoes carry only four or

five men, or at the most, ten or twelve; but our ships carry four or five

hundred, and sometimes a thousand. Others go to war by land, and in such

numbers that if they stood in a double file they would reach from here to

Mississaquenk, which is more than twenty leagues off. When our King attacks his

enemies, he is more terrible than the thunder: the earth trembles; the air and

the sea are all on fire with the blaze of his cannon: he is seen in the midst

of his warriors, covered over with the blood of his enemies, whom he kills in

such numbers, that he does not reckon them by the scalps, but by the streams of

blood which he causes to flow. He takes so many prisoners that he holds them in

no account, but lets them go where they will, to show that he is not afraid of

them. But now nobody dares make war on him. All the nations beyond the sea have

submitted to him and begged humbly for peace. Men come from every quarter of

the earth to listen to him and admire him. All that is done in the world is

decided by him alone.

But what shall I

say of his riches? You think yourselves rich when you have ten or twelve sacks

of corn, a few hatchets, beads, kettles, and other things of that sort. He has

cities of his own, more than there are of men in all this country for five

hundred leagues around. In each city there are store-houses where there are

hatchets enough to cut down, all your forests, kettles enough to cook all your

moose, and beads enough to fill all your lodges. His house is longer than from

here to the top of the Sault,--that is to say, more than half a league,--and

higher than your tallest trees; and it holds more families than the largest of

your towns.

The Father added more in a similar strain;

but the peroration of his harangue is not on record.

Whatever impression this curious effort of

Jesuit rhetoric may have produced upon the hearers, it did not prevent them

from stripping the royal arms from the post to which they were nailed, as soon

as St. Lusson and his men had left the Sault; probably, not because they

understood the import of the symbol, but because they feared it as a charm.

(The following is

from Thwaites,

Reuben Gold, The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents: Travels and

Explorations of the Jesuit Missionaries in New France, Vol. LV - Lower

Canada, Iroquois, Ottawas, 1670—1672, Cleveland, Ohio: The Burrows Brothers

Company, http://puffin.creighton.edu/jesuit/relations/relations_55.html)

Following this speech, Saint Lusson took

the word and stated to them in martial and eloquent language the reasons for

which he had summoned them, and especially that he was sent to take possession

of that region, to receive them under the protection of the great King whose

panegyrie they had just heard, and to form thenceforth but one land of their

territories and ours.

The whole ceremony was closed with a fine

bonfire which was lit toward evening, and around which the Te Deum was sung to

thank God.

(The following is

from the Wisconsin Historical Society):

In order that no one

plead cause of ignorance [of the events which took place, Saint Lusson records

the minutes of the ceremony (“proces-verbal”) and has all those present sign

it]:

Signed by us and the

under named persons who were all present.

Done at Ste Mary of the Falls [Sault Ste Marie] on the 14th June in the

year of Grace 1671, in the presence of:

1.

Reverend Father Claude d’Ablon, Superior of the missions in this

Country, of the Company of Jesus (Jesuits)

2.

Rev. Father Gabriel Dreuillettes, of the Company of Jesus (Jesuits)

3.

Rev. Father Claude Allouéz, of the Company of Jesus (Jesuits)

4.

Rev. Father André, of the Company of Jesus (Jesuits)

5.

Sieur Nicolas Perrot, his Majesty's Interpreter in these parts

6.

Sieur Jolliet from Trois Rivieres

7.

Jacques Mogras, from Trois Rivieres

8.

Pierre Moreau, Sieur de la Touppine, soldier belonging to the garrison

of the Castle of Quebec

9.

Denis Masse

10.

François de Chavigny, Sieur de la Chevriottiere

11.

Jacques Lagillier

12.

Jeanne Maysere

13.

Nicolas Dupuis

14. François Bibaud

15.

Jacques Joviel

16.

Pierre Porteret

17.

Robert Duprat

18.

Vital Driol

19.

Guillaume Bonhomme

20.

and other witnesses.

(Signed) Daumont de

Saint Lusson

After having participating in this ceremony, Francois returned safely to Quebec. Perhaps it was during this voyage that he formed the Outaouais a society with the discoverer Jolliet (notary Becquet 4 Oct 1675).

Today, the OASIS OF PEACE GARDEN commemorates this event: In the approximate geographical centre of North America stands a Symbol of Spiritual Unity. Here and on the American side of the International Bridge in Michigan's identically named Sault Ste. Marie, occupants and visitors can view the spectacularly lit 120 foot high Canadian Cross. The attractive Oasis of Peace Garden at the base overlooks the scenic St. Marys River and distant hills.

Source:

http://www.angelfire.com/id/multicultural/cross1.html

http://www.angelfire.com/id/multicultural/cross2.html

Francois

Bibaud and Jeanne (Chalifou) Bibaud – 1671 to 1682

Francois returned from his voyages to the Outaouais and Sault Ste Marie in early August 1671.

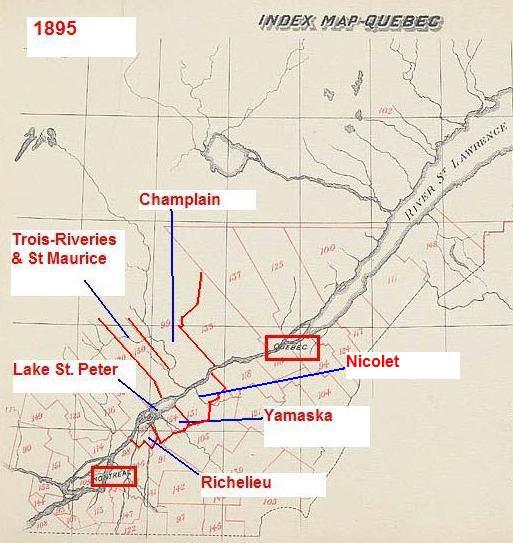

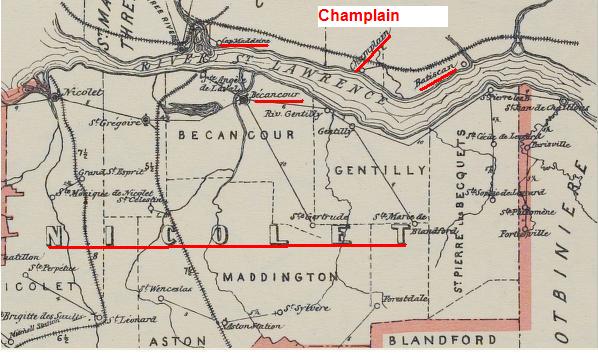

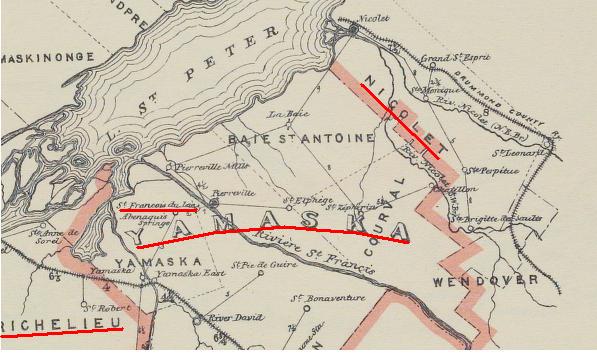

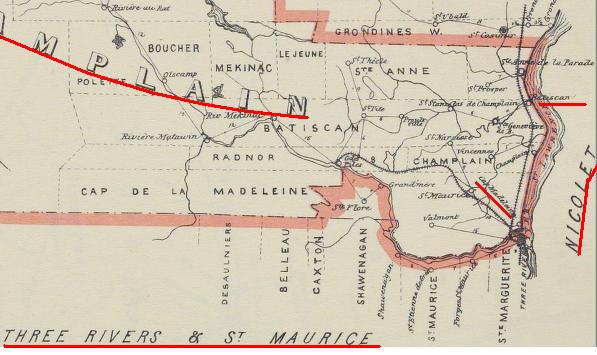

From 1671 to 1682, Francois seems to have

lived or had land concessions in various places along the St. Lawrence River in

the counties of Nicolet, Yamaska, Champlain, and Richelieu.

On 17 August 1671, after three years of engagement, Francois married his first wife, Jeanne Chalifou at the church of Notre-Dame-de-Quebec. They eventually had one child, Marie, born on 12 septembre 1674 in Becancour, in the county of Nicolet, located on the east bank of the St. Lawrence River:

Source: 1911 map, county of Nicolet http://data6.collectionscanada.ca/exec/getSID.pl?f=e/e034/e000835633&cat=sid&X110=1895&l=e&p=1&t=na04

On 24 January 1672, he sold to Mathurin Guillet his dwelling at Batiscan in the county of Champlain for the price of 400 livres and undertook a voyage to the area of Outaouais where we find him in 1673.

On 6 August 1673 Michel Godefroy ceded him some land three acres wide by one quarter a league in depth at Saint-Michel, in the county of Yamaska, located east of Lake St. Peter and the St. Lawrence River.

Source: 1911 map, county of Yamaska http://data6.collectionscanada.ca/exec/getSID.pl?f=e/e034/e000835656&cat=sid&X110=1895&l=e&p=1&t=na04

Francois lived at the Seignary of Linctot (in

Becancour, county of Nicolet) between 1674 and 1681 as the census of

1681 places him (Sulte) with 6 acres of toiled lands.

On 14 May 1674, Father Nicolas, Procurerur

of the Jésuites of Cap, ceded him some new land four acres wide at Batiscan

(county of Champlain), but he returned again to Outaouais during the summer

giving power of attorney from 16 August 1674 to Étienne Landron to act in his

name during his absence.

It is thought that he lived by the river

Puante when, on 4 October1675, his attorney gave a receipt to Louis Jolliet, in

his name, in the amount of 60 livres for settling his accounts and 25 livres 18

sols and 6 small coins for a bundle of beaver skins left in the hands of sister

Leber in Montréal.

In early 1679, after nine years of

marriage, Francois’ first wife, Jeanne Chalifou, died. Francois was elected trustee of her estate

and that of his daughter Marie on 10 April 1679. An inventory of her estate was concluded by

the notary Adhémar on the 20 March 1680.

He lived then on his land at Saint-Michel in the county of Yamaska where Mathieu Rouillard promised on the 20 January 1680 to deliver to him twenty minots of wheat at 3 livres a minot.

He then settled at Saint-François-du-Lac

in the county of Yamaska where he received two concessions (land grants), one on

the 1 March 1680 and another on the 30 March 1680, at St-Jean Isle, or Ile St.

Jean (notary Adhemar).

Francois and Louise (Esnard) Bibaud – 1682 to 1716

From 1682 to 1716, Francois seems to have lived or had land concessions in various places along the St. Lawrence River in the counties of Yamaska, Trois Rivieres, Nicolet, Champlain, and Richelieu.

On 9 October 1682, three years his first wife died, Francois signed a third marriage contract (notary Ameau), for marriage with Louise Esnard. Louise Esnard was born at Saint Jean de La Rochelle the 6 October 1668 at St-Jean, La Rochelle, Aunis. Francois and Louise were married at Trois Rivieres on 17 November 1682.

They had nine children:

- Pierre, born 6 Oct 1685 in Sorel, in the county of Yamaska.

- Unknown child, died soon after birth and buried in Aug 1687 in city of Trois-Rivieres.

- Francois, born 7 Mar 1689 in St-Jean-Baptiste in the county of Nicolet.

- Nicolas, baptised

on 7 May 1691 in Batiscan in the county of Champlain.

- Jean-Baptiste, born 3 Aug 1693 in Batiscan in the county of Champlain.

- Simon, born 18 Feb 1696 in Batiscan in the county of Champlain.

- Marie-Anne, baptized 24 Feb 1698 in Batiscan in the county of Champlain.

- Simon, born 18 Jul 1699 in Cap-de-la-Madeleine, in the county of Champlain.

- Joseph, born 15 Aug 1702 in St. Francois-du-Lac, in the county of Richelieu.

For a history of the Parish churches at Batiscan and St. Francois-du-Lac, see the end of this section.

Source: 1911 map, county of Trois Rivieres

Source: 1911 map, county of Champlain

Source: 1911 map, county of Richelieu

http://data6.collectionscanada.ca/exec/getSID.pl?f=/e/e034/e000835874&cat=sid&X110=Quebec

As a result of these two marriages, Francois had a total of ten children, one from his first wife and nine from the second.

On the 27 February 1684, at Saint-François-du-Lac, in the county of Yamaska, the Seigneur Jean Crevier ceded him some land two acres wide by forty acres (notary Adhemar). This was in addition to his two other land concessions in the same area in 1680.

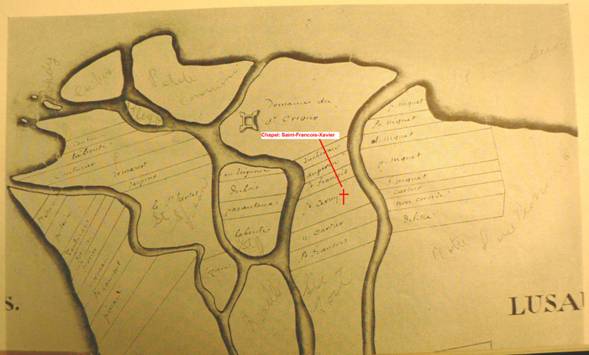

Below is a map from 1709 of the Domaine de St. Crevier, and the island of St. Jean where Francois’ land was located. Following this map is a map from 2006 showing how the topography has changed as a result of the erosion and changing course of the St. Francois. River

Source: Google Earth

In 1689, Francois established himself for

10-20 years at Batiscan in the county of Champlain before returning to Saint-François-du-Lac

in the county of Yamaska.

On the 23 March 1700, he ceded to Paul

Chalifou, in the name of his daughter Marie, that part of Paul Chalifou’s

inheritance due him from his grandfather’s estate. Francois obtained for Marie 85 livres.

On 29 January 1704, Francois relinquished his

land grant at Ile Saint-Jean, so that it returned to the realm of the Seigneur

of Saint-François (Crevier).

Francois died at Saint-François du-Lac

in the county of Yamaska in either 1708 or 1712. The latter date is most likely as his estate

was not settled until 1713:

A decree of the

sovereign Council 3 Jul 1713 said that Pierre Bibault (Francois’ son and first

child of his second wife) would "be paid by preference on the possessions

of his deceased father 300 Livres dowry of his deceased mother and other

amounts he will justify having paid for the funeral of his father and the

furnishings during his last illness.”

Francois’ second wife, Louise Esnard, was buried 18 January 1716 at St-François-du-Lac in the county of Yamaska.

Both Francois and his

second wife, Louise Esnard, died at St-Francois-du-Lac between 1708 and 1716. Based on these dates and the history of the

parish, both would most likely have been buried near the small mission chapel

located on the Ile de Fort (probable sight of the newer church,

Notre-Dame-des-Sept-Douleurs). The

chapel at this sight was demolished between 1850 and 1854 as it was being

replaced by a new church constructed in town.

For a history of the parish, see the end of this section.

According to Al Dahlquist: There are over 7,000 descendants of Francois who were born with the name Bibeau and its various spellings. There are probably another 3,000 yet to be connected to his tree.

New France between 1691 and 1847

Nicolas

and Marguerite Bibaud (Emily’s 4x great grandparents)

The fourth child of

Francois and Louise (Esnard) Bibaud was Nicolas, born in 1691, and baptised on 7

May 1691 in Batiscan, in the county of Champlain.

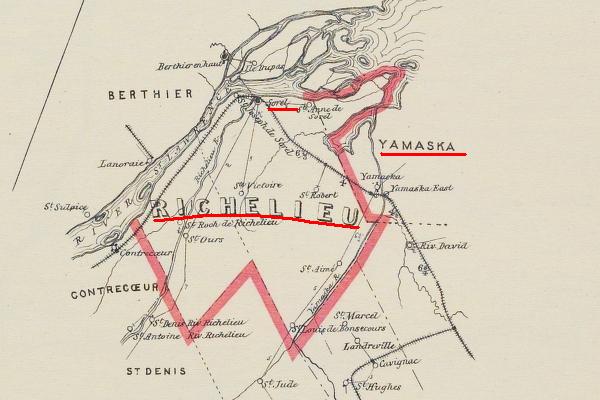

Nicolas married Marguerite Pelletier on 1 February 1717 in the church of St-Pierre-de-Sorel, in Sorel, in the county of Richelieu.

They had seven

children between 1721 and 1730, all born/baptised at St-Pierre-de-Sorel in Sorel:

Michael

Antoine

Enfant, died at birth

Marie-Therese

Joseph (our ancestor)

Marie-Rose

Pierre

Joseph and Marie Anne

Bibaud (Emily’s 3x great grandparents)

Joseph was born on 26

January 1727 in Sorel, in the county of

Richelieu, in the province of Quebec, Canada.

He married Marie

Anne Boissel in St-Francois-du-Lac on 2 Nov 1727.

They had six children

between 1752 and 1775, all baptised in St-Pierre-de-Sorel:

Joseph, died as an enfant

Nicolas

Joseph Alexis (our ancestor)

Antoine, died as an enfant

Louis

Herman, died as an enfant

Joseph Alexis and Marie Bibeau (Emily’s 2x great grandparents)

Joseph Alexis Bibeau was born in town of Sorel, in the county of Richelieu, in the province of Quebec, Canada, on 17 Aug 1758. He was baptized on 20 Aug 1758 at the church of St. Pierre de Sorel.

He married Marie Anne Desrosiers (Desrocher or Dutremble) on 7 Feb 1780 at the church of St. Pierre de Sorel. They had 12 children between 1781 and 1801, all of whom were baptised at the church of St. Pierre de Sorel, Sorel.

They had twelve

children between 1781 and 1801, all baptised either in St-Pierre-de-Sorel,

or in Quebec City:

Alexis, died young

Michel Antoine

Pierre

Jean-Baptiste

Joseph, died young

Angelique Judith

Joseph

Louis, may have died young

Hypolite

Marie Josette

Louis (our ancestor)

Parish Churches in Canada

This section contains

a brief history of the some of the parishes to which our Bibeau ancestors

belonged.

Parish of St-Francois-Xavier,

Batiscan, Quebec

Parish of

St-Francois-Xavier, St-Francois-du-Lac, Quebec

Parish of St-Pierre-de-Sorel, Sorel,

Quebec